The Silence Beneath the Surface

a journey through mercury, memory, and the waters that raised us.

How private memory intersects with the public commons. How one river’s story echoes through a continent of wounded waters. This piece traces the way personal lineage, colonial inheritance, and ecological harm braid together — and what becomes possible when we finally stop looking away.

Dedicated to the waters that raised us — and to the ones we failed to protect. To Eagle Creek and the Milwaukee River, to the White River and the runoff-stained streams of Appalachia. To the childhood creeks that never saw an eagle, the rivers that turned hypoxic—green and brown with dying algae, and the ones that taught us wonder long before we understood what had been taken from them.

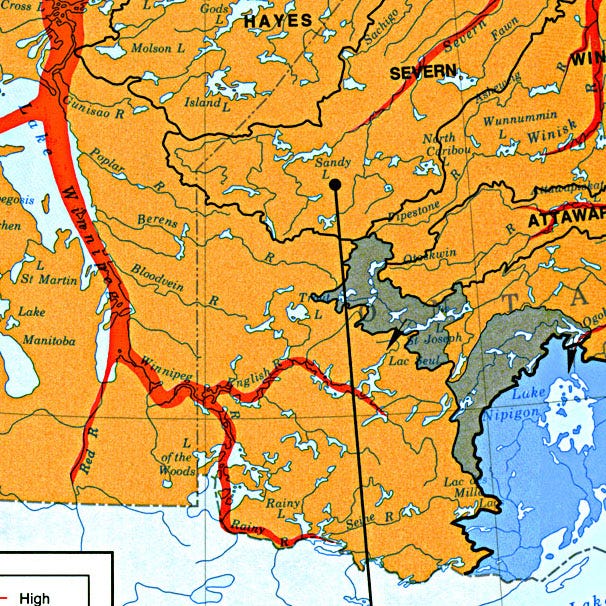

The English–Wabigoon River Before and Through Contamination

Before the contamination, the English–Wabigoon River system in northwestern Ontario was one of the great northern waterways — a long corridor of clean water, old forest, muskeg, and quiet bays where walleye, pike, and sturgeon moved in rhythms older than settlement. For Anishinaabe communities like Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong, the river was more than sustenance: it was identity, ceremony, medicine, relationship. Knowledge of spawning grounds, traplines, berry patches, and travel routes moved through families the way others pass down heirlooms.

For the settler families who came later — cottage owners, sport fishers, seasonal workers — the river became a place of retreat and imagination. A landscape that shaped memory across generations.

Then the shift began. In the 1960s, a chlor-alkali plant in Dryden released tonnes of mercury into the English–Wabigoon River watershed. The toxin settled quietly into sediment and moved up the food chain. Fish that had fed communities for millennia became hazardous within a few seasons. The commercial fishery collapsed. Neurological symptoms consistent with Minamata disease spread through Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong families. Governments minimized, delayed, denied. The river remained beautiful on the surface while carrying a wound underneath. That split — pristine appearance, poisoned reality — is the ground every story here stands on.

The River That Held What We Didn’t Want to See

My grandfather knew about the mercury long before I was born. Everyone on that river did. The warnings passed down like the location of a secret fishing hole. I grew up with old shoreline photos of pike and walleye, my grandfather grinning ear to ear. His gear survived into my childhood like artifacts from a world I never got to meet.

My father inherited the silence the way he inherited the boat and the stories. When we cleaned walleye on glacier-smoothed rock, he’d tap the spine with his knife:

“They shut this river down in the 60s and 70s because of the mill. When it reopened the fishing was outstanding.”

I didn’t know what he meant. I didn’t know what the river carried. Children trust the script they’re given.

That was my initiation — not into land-based knowing, but into soft colonization of the mind. Into believing surface beauty meant safety. Into overriding my own sensing because the adults did. Into learning affection without responsibility, belonging without history. I didn’t understand that the first thing colonization steals is the capacity to feel the wound beneath the surface.

By the time the English River found me, the contamination wasn’t a mystery — it was background. Familiar. Normalized. We treated the river like we treated our lineage: harmed, but beloved; broken, but approached as if the breaking didn’t matter.

When people disconnect from their own pain, they normalize the pain of the land. When colonial harm becomes background noise, environmental harm slides into the same category.